The idea in brief

- The recent Opal and Mascot Towers apartment building failures reveal a messy set of inconsistent laws, nationally, that discriminate between homeowners and apartment owners, undermining confidence in the residential apartment sector.

- In most States and Territories in Australia, homeowners are protected by statutory warranties that when complete, each new home will be free from defects for a warranty period.

- Most States and Territories also legislate for the requirement of a home warranty defect insurance policy that covers the cost of rectifying defects in homes if the builder goes broke, dies or disappears before fixing them (known as a ‘last resort’ policy).

- In Queensland, unlike other states, the home warranty insurance is even better because it operates on a ‘first resort’ basis. This means the builder does not need to become insolvent or disappear before the policy comes into effect, circumventing the need for the homeowner to first instigate time-consuming legal proceedings to have defects rectified. The Queensland scheme also insures against building subsidence or settlement, in addition to defects and non-completion of work.

- Apartment owners on the other hand are not as fortunate.

- For new apartment owners in apartment buildings of four or more storeys in Queensland, WA and three or more stories in Tasmania, no statutory warranties apply. Whereas, in New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia statutory warranties do apply to multi-story apartment developments.

- Unlike for new homes, no defect warranty insurance policy applies to new apartment developments (over three storeys in height) in any State or Territory in Australia.

- This leaves apartment owners and their bodies corporate to fend for themselves if defects are found in apartment buildings after construction is completed and they have taken occupation. Often that involves engaging lawyers and experts to attempt to sue the builder and/or developer. Apartment owners are left to assume the risk where they can be left out of pocket for hundreds of thousands, or even millions of dollars in legal and experts’ fees, and rectification costs in addition to the not unusual two-to-three-year period of litigation time that complicated construction disputes can take.

- To complicate the landscape further, NSW introduced a novel scheme in 2018 where developers of new residential strata apartment developments are required to lodge a bond equal to 2% of the construction cost of the apartment development, which is then held for 2-3 years by the NSW Department of Fair Trading. The body corporate / owners corporation of the building can then claim against that bond to rectify defects discovered in a final inspection, undertaken by an independent building inspector approximately two years after completion, should the developer have failed to have them rectified beforehand. No other State or Territory has followed suit in adopting this scheme.

- The current maze of disconformity of remedies and consumer protection between homeowners and apartment owners and between States in Australia is disconcerting for apartment investors and investors.

- The publicity of the Opal and Mascot Towers situation provides the momentum and should deliver the political impetus for State Governments in Australia to co-ordinate a response and produce uniform legislation and policy, restoring confidence to the apartment sector, delivering greater accountability of builders of apartment buildings about the integrity of their apartment product, and bolstering consumer protection and confidence for apartment purchasers.

-

A coordinated response to this issue by State Governments could involve:

- Uniform statutory warranties in each State and Territory, given from the builder, for homes and multi-story apartment developments, to owners and subsequent purchasers, imposing a minimum statutory warranty period for major and structural defects (and a lesser period for minor defects). A statutory warranty imposing a duty of care on any engineer or designer who designed the structure both to new owners and subsequent owners, for that warranty period, could also be legislated;

- A uniform statutory insurance scheme that covers both homes and apartment dwellings, which operates on a first-resort basis (similar to the home warranty insurance scheme already in place in Queensland for homeowners) and is administered by the building regulator in each State/Territory that regulates building licencing, compliance and prosecutes breaches of licences by builders and other construction practitioners; and

- Consistent national standards for building industry licencing and compliance of builders (including qualification, experience and financial holding requirements commensurate with the size of the development projects they seek to undertake), and other building practitioners such as designers, engineers, certifiers, etc.

….

The idea in detail

For most, the purchase of a home or an apartment in a high-rise development is a major lifetime investment.

The drama that has unfolded at Opal Tower and now Mascot Towers in Sydney involving significant design and construction defects that have called into question the structural integrity of those relatively new apartment towers, and removed families from their homes indefinitely at short notice with the prospect of financial ruin, is something most reasonable Australians would consider should not happen in a modern, well-regulated, first-world economy like ours.

Most apartment purchasers do not contemplate the possibility that a recently completed or soon-to-be constructed apartment block which they are considering acquiring a unit in might not be structurally sound. Reliance is instead intuitively placed on the belief that a major development of that scale ‘must have’ been signed off by engineers and certifiers, constructed properly and that government regulation is surely tight enough to prevent a catastrophic lapse of building standards on that scale.

What protections exist under the laws in Australia for apartment purchasers and how can they be improved?

The current protections are a mess

At the moment, the answer is: it depends.

It depends on the State or Territory the development is carried out in.

In some States, apartment owners (and often subsequent purchasers) have the benefit of statutory warranties that the building will be free from defects. These statutory warranties are deemed to be given by the builder and, in one state (NSW), also the developer. However, this is not always the case.

For example:

In NSW, new apartment owners (and subsequent purchasers) have rights against both the developer and the builder for breach of a range of statutory warranties, including the work not being carried out with due care and skill, use of poor building materials, that the work performed by the builder was done without due diligence, is not fit for purpose, or not reasonably fit for occupation.

These statutory rights exist for a period of six years from completion of the works for ‘major/structural defects’ and two years from completion of the works for other defects (slightly extended if the 2% building bond scheme referred to below applies).

In Victoria, new apartment owners (and subsequent purchasers) have similar rights to apartment owners in NSW in the form of similar statutory warranties but they are against the builder only, not the developer. However, unlike NSW, these rights exist for ten years (given recent case law in Victoria) for all breaches, not six or two years. In South Australia, slightly different warranties apply, but for only five years from completion.

At the opposite end of spectrum, in Queensland statutory warranties exist for new homes, but not for apartments in multi-story buildings of four or more storeys. A similar position applies in Tasmania but for multi-storey apartment buildings of three or more storeys.

In WA no statutory warranties apply at all (for homes or for apartments), other than an implied four-month defect liability period implied within certain residential building work contracts.

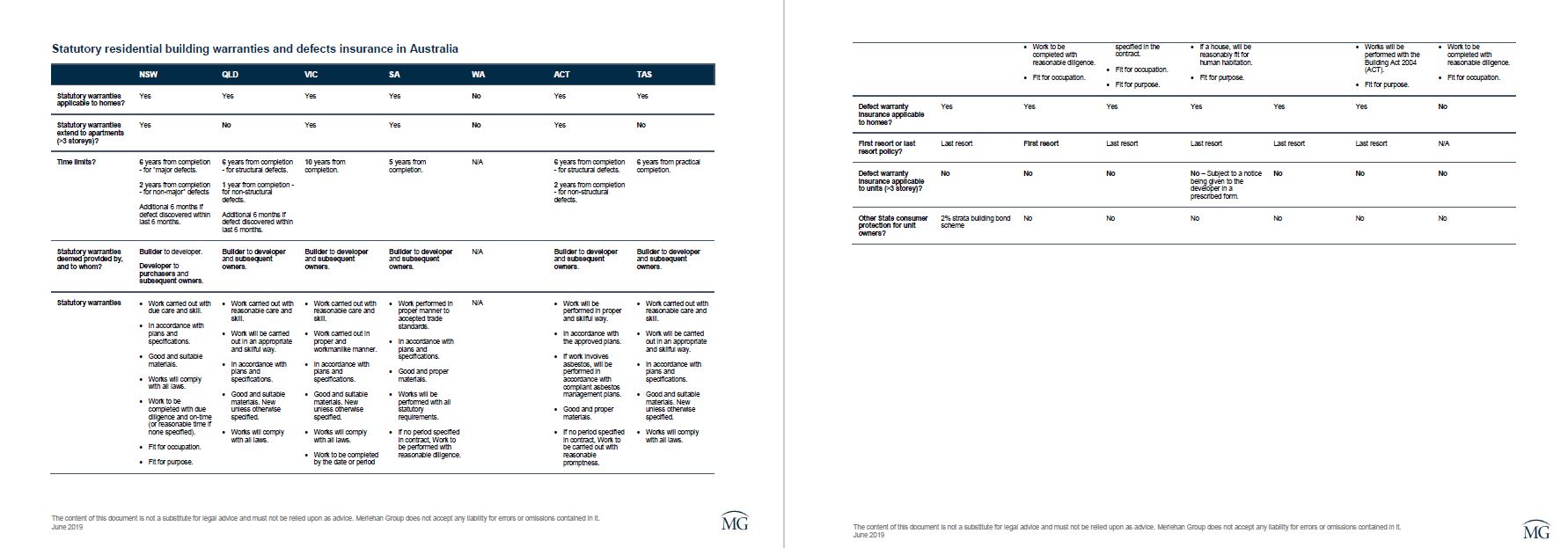

The table at the end of this article highlights the differences between each State (including SA and ACT), in more detail but it suffices to say, there is no consistency.

To complicate the landscape further, New South Wales recently introduced a novel regime requiring developers of strata title developments to submit a bond equal to 2% of the cost of constructing the building, to be held for two to three years following completion of the development by the NSW Department of Fair Trading. The building is then inspected on two occasions by a building inspector to produce an interim and final building defect report, and the corporate body / owners corporation can claim against the bond to rectify defects identified in the final report. No other State has yet followed suit in introducing this scheme.

Why the focus on statutory warranties?

Statutory warranties are important. Without them, owners of apartment and homes may have limited rights if their property was defectively constructed.

Statutory warranties are promises deemed by law to be made by one party to another party (or class of persons).

Importantly, they cut across the terms of any contract between those parties.

Taking NSW as an example: both the developer and the builder of a new home or multi-story strata title apartment development are deemed to promise to each apartment owner (and subsequent purchasers) for the relevant warranty period:

- That the work has been or will be carried out in accordance with the Building Act 2004 (NSW);

- That the work has been or will be carried out in a proper and skilful way and in accordance with the approved plans;

- That good and proper materials for the work have been or will be used in carrying out the work;

- That if the work has not been completed, and the contract does not state a date by which, or a period within which, the work is to be completed — that the work will be carried out with reasonable promptness;

- If the owner makes known to the builder the particular purpose for which the work is required, that the work is or will be reasonably fit for the purpose.

These warranties apply for six years from completion (for major defects), and two years from completion (for non-major defects) (extended to align with the 2% bond regime, if it applies), and this is the case notwithstanding the terms of any off-the plan contract between purchasers and developers which might attempt to shorten the time period or exclude liability of the developer (or builder) for defects in the building.

Statutory warranties are important because without them, under common law in Australia an apartment owner is unlikely to have any right to sue a builder (whom they do not have any contract with) under the law of negligence for defective design or construction of the building (unless physical property damage or personal injury has occurred as a result).

They are also important because, in the case of suing a developer, most off-plan contracts usually seek to limit the developer’s liability for defects in the building to a short window of time and, again, similar to pursuing a builder, the owner is unlikely to have any claim under the law of negligence for the cost of rectifying defects in the building against the developer.

Without statutory warranties, the owner could therefore be left with little or no avenue for legal recourse to the builder or developer if the building was defectively designed or constructed.

What about insurance?

If the builder goes broke or refuses to fix the defect, does any insurance apply?

In short, for multi-storey developments, in all States and Territories the answer is: no.

Yet, for homes, the position is different.

In most States and Territories except Tasmania, a ‘last resort’ policy of defect insurance for the cost of rectifying defects applies for new house construction, but only if the builder goes broke or disappears before rectifying the defects. However, these policies do not apply to apartment owners in multi-storey developments and, even for those homeowners that are covered by such policies, they are of limited utility because the homeowner must first pursue the builder into insolvency or prove that the builder has disappeared, before the policy will apply. That process can involve hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees and years of court proceedings for complex construction defects.

In Queensland, a more useful form of home warranty insurance applies to new house construction and is administered by the Queensland building industry regulator. It represents the gold standard of consumer protection because, unlike for the other states, it operates on a ‘first resort’ basis which means the homeowner can claim on it immediately rather than waiting until the builder becomes insolvent or disappears before the policy will apply.

The Queensland policy requires the owner to make a complaint about a defect discovered in the home to the building regulator for investigation within strict time-frames from first discovering it. The policy then covers the cost of rectifying that defect if the builder fails to comply with a direction from the regulator to do so (up to generous monetary limits). The regulator then pursues recovery of the rectification costs from the builder if the builder fails to fix the issue.

This regime has been in place in Queensland since 1977, and like other States, it does not apply to multi-storey strata apartment developments. In terms of cost, premiums for the Queensland insurance tend to equate to between 0.5% – 1% of the estimated cost of construction of the home and are payable by the builder. Notably, the construction market in Queensland does not appear to have suffered as a result, and consumers in Queensland are able to purchase new homes with added confidence.

Why have the States not simply enacted uniform laws to address this issue?

Unifying consumer protection in the building industry across State boundaries was previously on the political agenda, but seemingly fell by the wayside

The concept of unifying construction consumer protection, at least for homeowners, across States and Territories, is not new. It was the subject of a Federal Government senate inquiry in 2007 into “Australia’s mandatory Last Resort Home Warranty Insurance scheme”.

The report resulted in four recommendations, including:

- That all parties receive a copy of the insurance certificate, summary of product and dispute resolution procedures. The committee recommends changing the name of the insurance.

- That COAG and the Ministerial Council on Consumer Affairs (MCCA) should pursue a nationally harmonised ‘best practice’ scheme of consumer protection in domestic buildings.

- That COAG and the Ministerial Council on Consumer Affairs should pursue a nationally harmonised scheme of detailed reporting of home warranty insurance.

- That home warranty insurance should be included in the National Claims and Policies Database.

Despite mentioning the operation of Queensland’s ‘first resort’ insurance regime in the report, and the fact that “many submissions to the inquiry highlighted the benefits of the Queensland model of home warranty Insurance”, the report failed to engage with the Queensland model and indicate whether it should be adopted elsewhere.

This issue was not missed by some members of the committee. Victorian ALP Senator, Senator Gavin Marshall went as far as to include a stand-alone section to the report titled ‘Additional comments by Senator Marshall’ which relevantly noted:

… I believe recommendation two does not go far enough. I have been convinced over the course of this inquiry that the committee should be recommending a nation-wide adoption of a form of Home Warranty Insurance that reflects the form currently in effect in Queensland.

It is my view that the Federal Government should take a leadership role on this issue and progress a Home Warranty Insurance model through COAG using the current Queensland model as a template.

In a dissenting report, the Greens noted:

Many submissions to the inquiry highlighted the benefits of the Queensland model of home warranty insurance. …The Greens concur that this scheme represents best practice in Australia and has the support of consumer advocates and builders alike.

So what has happened since the Senate Report?

The answer, it seems, is, unfortunately, not much.

On May 8, 2009 the Senate Committee Report was referred to the Standing Committee of Officials of Consumer Affairs (SCOCA). The SCOCA minutes of meeting noted:

MCCA noted the findings of the Senate Economics Committee’s report into Australia’s mandatory last-resort home builders’ warranty insurance (HBWI) scheme and agreed to refer this matter to SCOCA to consider as part of the review of the harmonisation of conduct provisions for the national licensing system. Ministers agreed to place this issue on the MCCA Strategic Agenda.

Despite the above, no further mention of the issue in any further meeting minutes or ‘strategic agenda’ of SCOCA can be found in publicly available information, and there certainly has not been any uniform reform implemented since.

While, historically, other priorities and a public policy distinction based on the cost difference between the construction of a multi-storey apartment tower versus a single home may have existed to justify the current differences in the consumer protection measures available to unit owners versus homeowners, as the densification of city living continues apace, any such policy distinction is increasingly difficult to sustain.

Australians living in cities in each State are now increasingly adopting medium and high-density apartment-style living and this needs to be encouraged to lessen the demand for new public infrastructure spend caused by continued unabated urban sprawl.

What solutions exist?

One proposed solution: is a three-pronged approach

A three-pronged approach involving the following reforms is one possible solution:

- Uniform statutory warranties;

- Uniform defects insurance; and

- Uniform building and engineering licencing and compliance regimes.

Each are dealt with below.

-

Uniform statutory warranties

It is obvious from the above that the current state of play is unacceptable.

Some States provide statutory warranties in favour of apartment owners.

Some do not.

One does not provide any warranties at all, both for new homeowners, or apartment owners.

For those that do provide statutory warranties, they vary between the warranty period covered and the content of the warranties.

Consistency is needed.

A single agreed-on set of warranties, applicable for consistent time periods following completion of the build, should be legislated across States.

-

Uniform defects insurance

Development of state-run ‘first-resort’ insurance that covers both home and apartment owners, funded by premiums payable as a percentage of the construction contract value to the regulator (as is the case in Queensland), is worth investigating.

As is the case in Queensland, the risk insured may be reinsured through the re-insurance market, and reluctance of the primary insurance market to cover this defect risk can be ameliorated by a State-run regime.

Given the insuring regulator is also the regulator that licences and prosecutes non-compliance in the industry, and who should have statutory power to direct the rectification of defective building work, the State building regulator is best placed to bring about change in the market and uphold building standards.

Any profit made from running this ‘first resort’ insurance regime in each State could be funnelled back into industry education and compliance activity. Consumers would rest assured that their purchase of new off-the plan apartment or homes and subsequent purchasers who purchase the property during the insured warranty period are protected by statutory insurance against defects (up to appropriate monetary limits).

-

Uniform building and engineering licencing and compliance regimes

The poor and fragmented status of regulation in the industry across States and Territories in Australia has been well documented in the recent Shergold-Weir report which can be accessed here.

In short, a consistent approach to the establishment of state-based building regulators solely responsible for licencing and monitoring compliance of key participants in the industry: including builders, engineers, certifiers, electricians and other building practitioners, is required. A consistent approach to registration, compliance and continuous professional development of those building practitioners is also required.

For example, professional engineering services carried out in Queensland or for a Queensland project are required to be carried out by a professional engineer registered by the Board of Professional Engineers of Queensland (after assessment), or under the supervision of such a registered professional engineer. No other State has a similar requirement for registration of professional engineers. Most consumers would be surprised to learn this.

Similarly, consistent minimum financial backing and experience requirements as well as different tiers of builder licencing is needed to ensure builders that execute major multi-storey development projects are appropriately experienced and financially sound to back the considerable obligations they assume when building on that scale. The licencing regime for contractors currently varies greatly from State to State.

Towards a more consistent building industry regulatory landscape…

If the above three avenues of reform are pursued, the frequency of Opal Tower and Mascot Towers-like situations would be avoided or markedly reduced. Confidence would be restored to an important sector of the property market in Australia, and the safe, inevitable continued transition towards higher density metropolitan living in our cities would be better supported by harmonised national building industry regulation.

Click to enlarge:

The above constitutes opinion only and is not to be relied upon as legal advice for any matter. Any party seeking to use information contained within this post should first seek specialised professional advice. Merlehan Group and its personnel do not accept any liability for any errors or omissions in this post.