The idea in brief

- The frequency of use of Royal Commissions and Commissions of Inquiry (‘Commissions’) by Australian governments has doubled in recent years.

- Commissions have become prominent mechanisms to address and resolve public controversies and inform government responses.

- Engaging with a Commission involves considerable risk for businesses (including reputational, financial and legal), with law reform, litigation or prosecution often following the conclusion of a Commission.

- A robust process is necessary for businesses to navigate their participation in a Commission should it be called upon to provide evidence or participate as a witness.

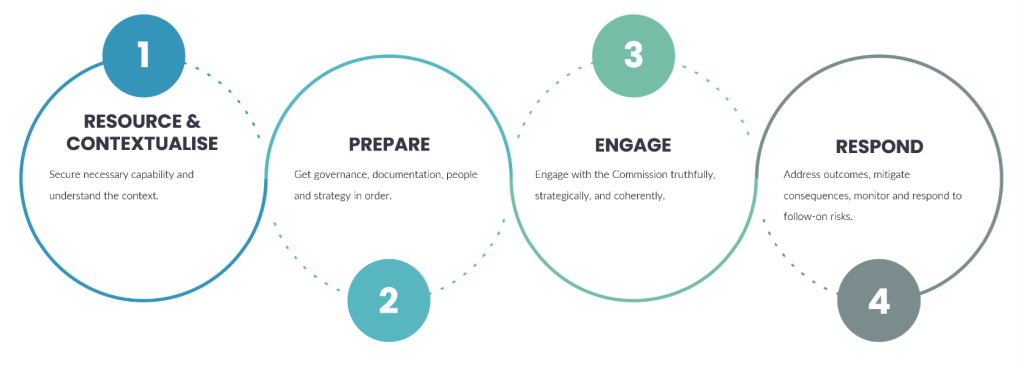

- We have developed a four-stage framework that in our experience is useful to consider when engaging with a Commission, where involvement with the Commission may be contentious.

- Stage 1: Establish Resources and Contextualise

- Notify insurers

- Review terms of reference and political context

- Assess risk of contention

- Engage legal team and PR expertise

- Stage 2: Prepare

- Establish internal governance

- Collate and review key business documentation

- Prepare potential witnesses

- Develop engagement strategy

- Stage 3: Engage

- Detailed preparation of witnesses required to give evidence

- Proactive review of Commission documents

- Attend witness interviews and public hearings

- Develop witness statements and submissions

- Stage 4: Respond

- Analyse Commission report and findings

- Brief board and executive on adverse implications

- Assess and respond to follow-on litigation, regulatory or reputational risk

- Stage 1: Establish Resources and Contextualise

- Each stage of the framework is explained in more detail below.

The idea in detail

Disclaimer: the information presented in this article constitutes a general commentary and should not be construed as legal advice. Given the unique circumstances which are inherent in each matter, readers are advised to seek specific legal counsel to ensure responsive advice which is tailored for their particular matter.

Introduction

When public trust and the legitimacy of government decision making are under scrutiny following a crisis, systemic failure, or where public policy issues or controversies arise, Australian governments often establish Royal Commissions, Special Commissions, or Commissions of Inquiry (‘Commissions‘) to investigate and recommend responses. These inquiries play a vital role in restoring accountability and shaping reforms.

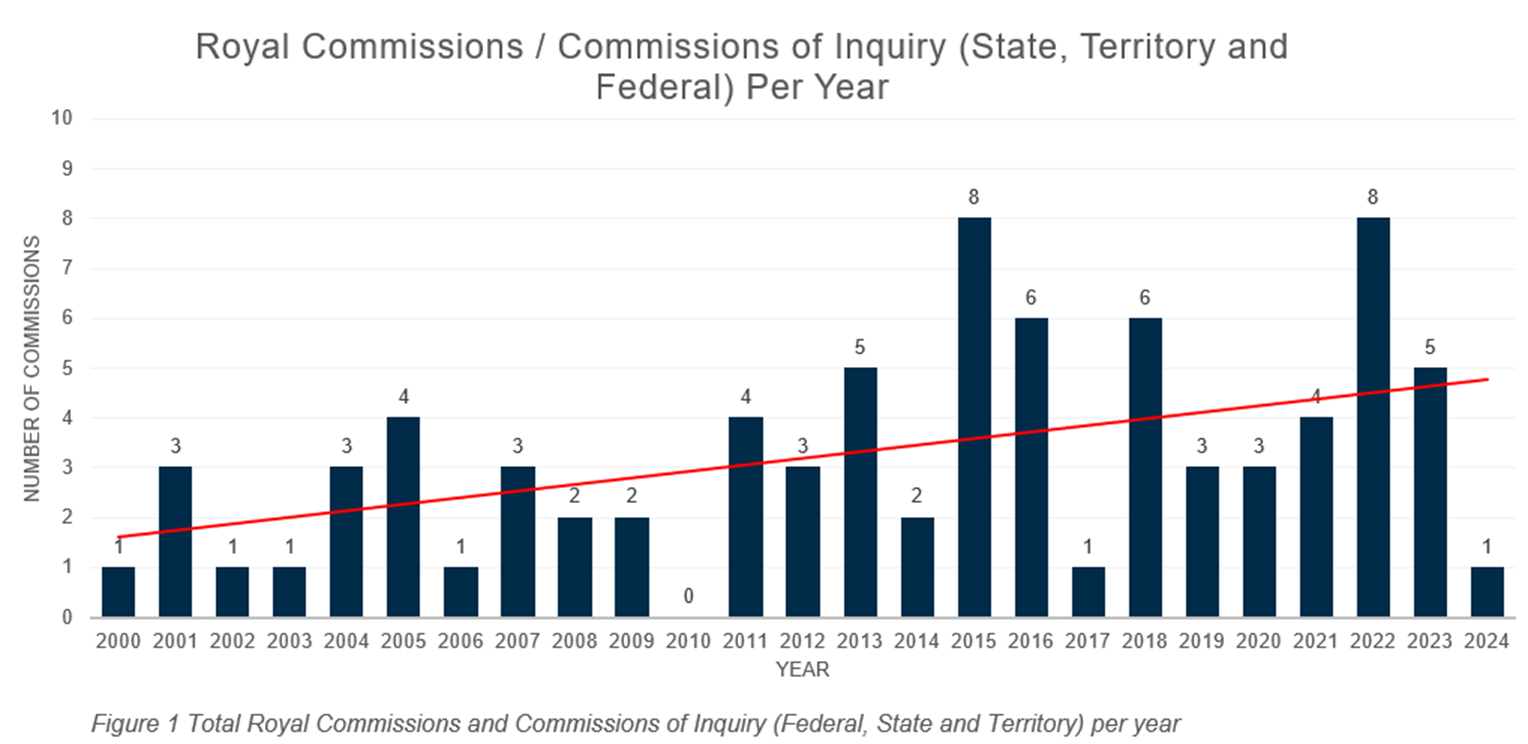

Rising Use of Commissions

The proliferation of Commissions in recent years reflects their increasing prominence as mechanisms for addressing public controversies, systemic failures, and corporate misconduct. The frequency of their use by governments in Australia have doubled in recent year. Between 2000 and 2012, Federal, State, and Territory governments initiated on average 2.1 Commissions per year. Between 2013-2024 this figure more than doubled to 4.3 Commissions per year.

Commission findings often drive legislative reforms which in turn directly affects businesses and compliance obligations. For instance, the 2003 Cole Royal Commission’s exposure of unlawful conduct within the building and construction industry resulted in the reestablishment of the Australian Building and Construction Commission (subsequently integrated into the Fair Work Ombudsman), with expanded monitoring, prosecution, and penalty powers. Similarly, the 2017 Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry and the 2018 Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety prompted major regulatory overhauls in those respective sectors.

Given this upward trend, it is important that businesses understand how to navigate potential involvement in a Commission to minimise risks the process poses to business.

What is a Commission?

Commissions are established under jurisdiction-specific legislation, such as the Royal Commissions Act 1902 (Cth) or the Commissions of Inquiry Act 1950 (Qld). Their scope is strictly defined by the “terms of reference” or “letters patent” issued by the appointing government, which establish a mandate to conduct an inquiry and report recommendations. Typically chaired by experienced legal figures such as current or retired judges or senior barristers, Commissions may also comprise co-commissioners with specialised expertise and support staff, including counsel assisting, researchers, and administrators.

Although designed to be run as an apolitical and independent inquisitorial process, Commissions are fundamentally initiated, scoped, and funded by governments.

Coercive powers and the risks posed to businesses

To gather evidence, Commissions are afforded coercive power to summon and compel witnesses to give evidence under oath before the Commission, and/or to require the production of documents before the Commission. Non-compliance is usually punishable by fines or potential periods of imprisonment under the enabling legislation and an individual’s right to refuse to answer questions or to produce documents to the Commission on the basis of privilege against self-incrimination is often excluded by the enabling legislation for the Commission.

Commissions also often call for and receive voluntary submissions from members of the public.

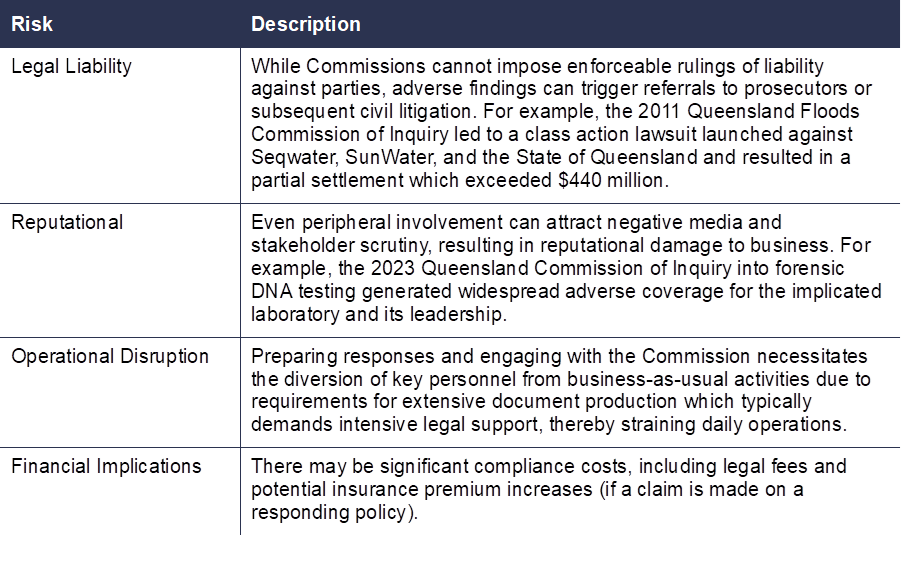

This public and inquisitorial Commission process poses substantial risks to those businesses engaging with the process:

Businesses need to approach Commissions cautiously, prioritising preparation to mitigate these risks.

A Framework for Planning a Response to a Commission

Our experience has revealed the following framework and insights that may prove useful to navigate the complexity of engaging with a Commission, particularly if the business’ involvement before the Commission is likely to be controversial or involves an appreciable risk of adverse findings being made against the business.

Stage 1: Establish Resources and Contextualise

Secure necessary capability and understand the context.

(a) Notify any relevant insurer

If the business has insurance cover that indemnifies the business for the costs of responding to a Commission (or other statutory investigation processes), notification should be made under that policy in order to access cover for the costs of dealing with the process. D&O, professional indemnity, and management liability insurance policies should be reviewed to see if they include coverage for the costs of dealing with the Commission.

(b) Carefully review the “Terms of Reference” or “Letters Patent” in detail

This is a key document which establishes the Commission and the scope of its inquiry into subject matters, and the terms under which the inquiry is to be made. Issued by the establishing government, it may provide information as to:

- the time period, events or conduct that is being reviewed: this enables an informed assessment of which business personnel may be summoned to give evidence before the Commission, which business records, documents, and emails may be required for production, and which of the business’s former employees may be approached to give evidence before the Commission.

- when the Commission is expected to conclude its work: this information will allow an informed estimate as to the anticipated degree, depth, and pace of the inquiry. A 6-month inquiry to report on a matter is likely to be more targeted than a 12-month inquiry for example. Shorter timeframes may intensify peak demand, underscoring the need for agile legal support.

This information will inform initial planning for meeting any relevant document discovery processes or giving of evidence that might ensue. Care should also be taken to identify any practice directions issued by the Commission which may provide further guidance on an engagement strategy.

(c) Analyse the political context and public sentiment behind the controversy for which the Commission has been called to inquire about

While the conduct of the Commission is an a-political process, it is the government of the day that decides to convene a Commission and that does not occur in a political vacuum or absent prevailing public sentiment. Understanding the political context and public sentiment driving the Commission’s establishment will allow for a reasonable assessment of the issues and lines of inquiry that are likely to be explored and may give context to any government departments or regulatory witnesses’ positions when called to give evidence by the Commission. It also serves to assist in gauging the ‘temperature’ of public interest in the inquiry process and predict the resultant levels of scrutiny those who do give evidence before the Commission may face.

(d) Assess contention risk

Assess whether the business’ involvement in the Commission presents any appreciable risk or potential for the Commission to make adverse findings against the business, its employed or affiliated witnesses. This also helps gauge media scrutiny, informing PR strategies (see Step (g) below).

(e) Engage external legal representation

Commissions are intensive by nature – they involve compulsion of witnesses by law to give evidence and produce documents, often at very short notice, and with very limited exceptions. The Commission is operating under time pressure to complete its inquiries, make and report those findings to Government. In this context, time is of the essence and extensions to deadlines to prepare materials, documents or for witnesses to appear before the Commission are uncommon.

The business must also continue as usual despite the pressures of engaging with a Commission. It is unlikely that in-house legal teams will have the excess capacity to solely handle the workload caused by responding to the rigours and demands of a Commission effectively without engaging external legal support and guidance.

Businesses should consider the benefit to be gained from engaging a dedicated external legal team that can strategically guide the business’ response to the Commission and support the process, without compromising the rest of the business’ BAU legal work.

(f) Retain Senior Counsel and Junior Counsel (if contentious)

If the business is required to produce documents, prepare submissions, or give evidence before the Commission, it is common to retain counsel and seek leave to appear with legal representation before the Commission.

For some Commissions it will be important to retain and brief counsel before they are retained elsewhere. This is especially important in cases where the Commission involves multiple parties who may each be seeking to retain counsel. In those situations, there will likely be competition to secure the most eminently qualified counsel for the subject matter of the Commission. It is therefore a disadvantage to delay retaining preferred counsel should the business perceive any material risk of contention.

When selecting counsel to retain, it is prudent to consider:

- the relevant counsel’s experience with Commissions;

- the relevant counsel’s experience with similar subject matter or controversy the Commission is investigating; and

- the expected operating ‘style’ and approach of the Commissioner(s) and Counsel Assisting the Commission, versus that of Counsel retained.

Depending on the nature of the Commission and the scope of its inquiry as well as the level of contention risk assessed in the earlier stages, Senior and Junior Counsel may be retained.

(g) Retain external public relations expertise if contentious

Commissions can involve controversial matters that attract media and public interest reporting. Depending on the level of contention expected for the business from the process, and extent of in-house public relations expertise, it may be prudent to also engage external public relations expertise to effectively assess and determine what is required to be managed before, during and after an inquiry, with respect to media messaging, requests for comments/interview and any public comment/response on any findings made by the Commission that affects the business.

Media engagement (if any) during the course of the Commission’s process needs to be measured and respectful of the ongoing Commission process and vetted by the legal team to ensure there is no risk that the publication would amount to a contempt of the Commission (under the enabling legislation for the Commission) or violation of any non-publication orders.

Media training of key witnesses who may be approached may be necessary, and a protocol for directing media inquiries to a dedicated public relations and communications team should be established, with oversight of the business’ executive.

Stage 2: Prepare

Get governance, documentation, people and strategy in order.

(a) Establish a committee

The business should establish an internal committee chaired by the general counsel of the business or external legal advisor, and comprised of a senior executive leading the relevant part of the business that may be related to the Commission’s work (and may include the CEO or Managing Director of the business on a standing invite basis), the head of risk and any corporate communications/public relations lead.

An initial briefing should be conducted at the first committee meeting with key executive members to ready the business for the Commission process, covering:

- a general overview of what a Commission is and involves, including the typical process;

- an overview of the terms of reference;

- protocols for maintaining internal hygiene concerning internal and external communications, including preservation of legal professional privilege and limiting inadvertent production of materials that could become discoverable during the process (or subsequent litigation or regulatory proceedings that could follow the Commission’s findings); and

- immediate next steps and priorities.

The purpose of the committee is to keep relevant stakeholders informed effectively on the process, whilst seeking to preserve legal professional privilege and control over the production of non-privileged materials, and will:

- serve as a key focal point for updates from general counsel during the process; and

- allow for key business leaders and market facing executives such as public relations and corporate communication representatives to be informed of the obligations of the business and its employees during the process and receive updates on the process.

It is recommended that a regular cadence of meetings be set up to establish an operating rhythm.

(b) Conduct initial overview meetings with key internal persons who may be called by the Commission to give evidence as witnesses

These meetings should provide a general overview of the Commission and the person’s expected role in giving evidence before it, including:

- the subject matter of the Commission and the likely scope of the person’s expertise upon which they may be examined;

- the general process, powers and nature of the Commission;

- encouraging the person to refresh their memory of the relevant events that may be the subject of the scope of the Commission’s inquiries, including by review of any relevant business records/documentation, noting a significant period of time may have elapsed between the matters being inquired about and the commencement of the Commission;

- cautioning potential witnesses to not confer with each other about evidence they may give if called as a witness.

Pastoral support should also be available for these persons given the process of giving evidence before a public Commission may be stressful – especially if their evidence is likely to be about a matter of controversy, or the subject of challenge, cross-examination or professional judgment or public comment by others.

(c) Before being compelled to do so, begin collating key documents in response to the “Terms of Reference” (or similar)

These documents will assist in:

- informing legal assessment of matters in issue and how the legal team can support in the matter;

- readying the business to comply with notices to produce if such notices are received; and

- allowing key witnesses to begin soft preparation to appear before the Commission.

By organising these documents early, the business can maximise the time available to prepare and increase the quality of its responses.

Additionally, consideration should also be given to whether information or answers to queries are voluntarily given or offered up to the Commission. Where voluntary disclosure is contemplated, it should be considered whether such information will attract immunity under the relevant enabling legislation from use in subsequent civil or criminal proceedings against that person, as some jurisdictions do not extend such protections to voluntary submissions.

(d) Understand background and experience of Commissioner and counsel assisting the Commission

It may be useful to understand the background and subject matter expertise of each Commissioner as these factors can provide useful insight into how the hearings are likely to be approached, operating styles, any specific subject matter expertise of non-legal commissioners may inform potential lines of technical inquiry of the Commission.

The importance of the role Counsel Assisting will play in the Commission’s process should also be acknowledged, while not making the mistake of conflating Counsel Assisting’s views or comments with those views of the Commissioner. Some Commissioners will lean more extensively on Counsel Assisting than others, however Counsel Assisting will play a key role in investigating facts, interrogating witnesses and shaping the conduct of the public hearings.

Counsel Assisting usually proves to be a useful point of engagement to resolve concerns regarding the scope of proposed notices to produce documents, witness appearance lists or timetables, or other procedural or interlocutory matters in advance of a formal application for determination by the Commission. It can be sensible to seek to resolve such issues collaboratively for subsequent approval of the Commission, rather than requiring formal hearings on contested issues for the Commission to rule on, unless this becomes necessary.

(e) Conduct a detailed review of key documentation available to the business that appears relevant to the Commission’s Terms of Reference, and develop a base chronology of key relevant events (if applicable)

This will require the discovery of key documents within the business, as well as review of the Commission’s documents (if they are made available for review), to inform a broad understanding of the nature of the issues likely to be in contention and at risk to the business.

(f) Conduct an initial interview with expected key witnesses in the business

The aim of these interviews is to:

- inform an understanding of the general matters in issue and further issues that need consideration;

- assist the legal team in identifying and informing the business progressively of perceived risk arising from the Commission’s scope of inquires;

- develop sufficient understanding of likely evidence the witness will be capable of providing and the nature of that evidence;

- inform decisions about whether any expert witnesses may be engaged and required to explain any key technical matters relevant to the “Terms of Reference” on which the Commission may make controversial findings; and

- identify the types of questions or cross-examination the witness may be subject to.

This will guide the business’ response strategy and ensure witnesses are adequately prepared for the process. Additionally, this step can help familiarise the witnesses with the lines of questioning they can expect from the Commission, direct the business as to what additional evidence or witnesses may be required, and reveal needs for experts in technical fields.

(g) Develop an initial strategy for responding to a Commission

While a Commission is primarily an inquisitorial process, it is incorrect to assume there will be no opportunity for effective advocacy to encourage the Commission to not make a certain finding of fact it might otherwise have been inclined to make absent the persuasive submission.

A decision may need to be made early about whether to adopt a proactive posture that seeks to engage with the Commission proactively to seek to uncover relevant evidence and endeavour to persuade the Commission with respect to any relevant findings that need to be made. Alternatively, in appropriate cases, a decision may be taken to adopt a ‘small-target’ strategy that seeks to engage only if compelled by the Commission to do so and, in doing so, in a limited, more reactive manner. The extent of contention expected for the business from the Commission’s inquiries and focus may inform this decision. This strategic decision will inform team composition, resourcing allocation and demand, and next steps in preparing for the Commission process as well as the degree to which legal counsel seeks to cross-examine other witnesses giving evidence before the Commission, for example.

Submissions and witness evidence produced to the Commission, as well as opportunities to cross-examine other witnesses giving evidence before the Commission (with leave of the Commission), can be used to:

- ensure that facts gathered by the Commission are properly understood or discovered within their proper context; and

- explain the relevance of this context and the client’s perspective to the Commission, so as to assist the Commission in arriving at proper findings of fact and to not unfairly make adverse findings against a party or a person who appeared before the Commission.

The above opportunities can be central to ensuring adverse findings are not inappropriately made against the business’ interests, avoiding any reputational or other damage that may follow.

Stage 3: Engage

Engage with the Commission, truthfully, strategically, and coherently.

(a) Prepare witnesses to give evidence

It is inappropriate to coach a witness giving evidence by advising what to say in response to any question, or encouraging a witness to give misleading evidence. In many jurisdictions, doing so may amount to an offence under the Commission’s enabling legislation. However, it is appropriate for legal advisors to assist a witness to prepare to give evidence by:

- explaining the process of giving evidence and what it will involve, including who may be in the room when they are giving evidence and what their role is;

- explaining witness’ jurisdictional-specific rights and, where applicable, providing advice concerning any exclusion of their right to rely upon the privilege against self-incrimination when giving evidence, and any specific protections afforded to the witness regarding subsequent use of that evidence against the witness in civil or criminal proceedings (where applicable in the enabling legislation and noting any specific qualifications on this protection, for example, does it apply to voluntarily supplied information? does it apply to documents produced or only statements or disclosures by the witness?); and

- providing an overview of the general conventions and practices of a working Commission;

- encouraging the witness to refresh their memory from the contemporaneous documentary evidence that may be relevant including relevant business records that have been discovered in preparing for the Commission;

- questioning and testing in conference the version of evidence to be given by a prospective witness including by drawing the witness’s attention to any identified inconsistencies or other difficulties with their evidence. It is imperative however, that the legal advisor does not encourage the witness to give evidence which differs from the evidence which the witness believes to be true;

- calling the witness’ attention to points that might arise during examination by the Commission (or cross examination where others appearing before the Commission have leave to cross-examine witnesses) and advising the witness as to the manner of addressing such questions. For example, generally instructing the witness to listen carefully to the question, be directly responsive to the question and as concise as possible is appropriate. However, this must not stray into coaching the witness as to the content of any answer to give to any such question.[1]

- when preparing witnesses, conferencing with more than one witness at the same time regarding an issue that is likely to be contentious should not occur to avoid the risk of either witness influencing the other’s evidence or recollection of the issue.[2]

It should be noted that the process of giving evidence before a Commission will likely be a foreign and confronting experience for most, especially for witnesses who are not legally qualified or familiar with court processes. In that regard, to pre-frame expectations from real world examples, a number of recent Commissions have been recorded and are available for viewing online. These videos may be useful resources in demonstrating the process of a Commission.

(b) Attend any interview required by the Commission with key witnesses

It is not uncommon in the process of the Commission’s inquiries for the Commission to require a person to attend its offices to sit a record of interview to assist its initial inquiries (before public hearings).

If this is required, the witness should be prepared for that interview, and legal counsel should attend the interview as (in addition to ensuring the witness is fairly dealt with) this provides an early opportunity to understand the lines of inquiry the Commission is pursuing in advance of any public hearings. Doing so may also inform legal preparation for the hearings, including preparation of witness statements.

(c) Keep an active watching brief on key Commission documents

Often the Commission will make available to those parties appearing before it, including their legal representatives, copies of the relevant documents the Commission has collected in relation to the issues. This is usually provided in the form of access to the e-room/e-discovery depository established for the Commission which may include witness statements and records of interview of other persons.

The legal team should avail itself of any opportunity to access such information for the sake of preparing witness statements and devising strategies for any public hearings as it may provide opportunities to furnish evidence or submissions which address contentious issues, retain expert witnesses to offer opinions on a matter of controversy which appear to be emerging from such material, and inform any potential for cross-examining other witnesses to ensure findings made by the Commission are properly informed.

This information should be kept confidential, not disseminated and only used strictly for the purposes of the Commission process and in compliance with any directions of the Commission regarding restrictions on use such as non-publication orders and any relevant practice direction.

(d) Develop witness statements (if provided the opportunity to do so, in addition to any interview)

A Commission can receive evidence in whatever form it wishes and will usually set its own rules for receiving evidence, however it is common for a Commission to allow parties to produce witness statements of witness evidence. If this opportunity is provided, it is usually sensible to take it, although a strategic call may need to be made in light of the situation at hand.

Often, these statements will assist the Commission in receiving evidence in an orderly way so as to assist in it understanding the context of each witness’ evidence.

While the record of interview will be tendered by the Commission, a witness statement can better organise evidence compared to what may have occurred verbatim, provide additional information or context to what was said in the interview, address any important issues not covered during the interview process, and if necessary seek to correct any error or oversight during the interview.

(e) Begin developing submissions early

Like other legal processes, it is important to allow as much time as possible to prepare formal submissions to the Commission in order to enhance its quality and persuasive impact – particularly where time can be in short supply in a compressed process like a Commission.

It can become apparent during the course of the Commission’s hearings that a particular issue is a vexed issue that the Commission will be required to make a finding about. Where that issue is a matter of some controversy that may affect the client, preparation of relevant submissions should begin early (for example, during the course of the Commission’s hearings), particularly if the legal team possesses capacity to commence such work.

Finally, natural justice and procedural fairness usually ensures that parties and witnesses who have given evidence before the Commission are provided with an opportunity by the Commission to be informed in advance of adverse findings proposed to made by the Commission against that party as may be published in the Commission’s report. This usually includes details of the nature of those findings the Commission is considering making against the party, and why the Commission considers there is basis to make such findings. The person or party is then usually provided with the opportunity to provide formal written submissions in response to those potential adverse findings, which should usually be taken if provided.

Stage 4: Respond

Address outcomes, mitigate consequences, monitor and respond to follow-on risks.

(a) Carefully review any report of the Commission released (usually by Government) after the conclusion of the Commission

The Commission will usually present its report to government at the conclusion of its inquiry. The Government will then typically prepare a response to the report and any recommendations in it and release both the Commission’s Report and the government’s response to it publicly.

If that occurs, those documents should be promptly and thoroughly reviewed by the legal team to ensure the identification of any potential adverse outcomes or findings for the business, while monitoring government responses for reform impacts.

(b) Brief executive and board on any adverse findings or opportunities

Any adverse findings or implications to the business resulting from the Report should be briefed to the leadership team and board. Similarly, if the Report identifies any lessons learned that may be of value to the business’ activities that could be implemented in the business, these too should be captured.

Care should be taken to preserve legal professional privilege over any legal advice in this process so as to avoid the generation of discoverable material opining on perceived risk of implications or conduct the subject of the Report.

(c) Assess and monitor risk of follow-on civil ligation, regulatory prosecution or reputational damage

If the Report contains adverse findings against the business or key witnesses that pose reputational damage or litigation risk, then work may commence on a defence strategy and public relations response to address those issues. A government relations and stakeholder engagement strategy may also be necessary to minimise any potential regulatory reform overreach which would adversely affect the business or industry. Industry body associations may serve as a useful vehicle for advocacy in this respect.

Key Takeaways

Being called to give evidence before a statutory inquiry such as a Royal Commission, Special Commission or Commission of Inquiry involves intensive processes that require careful management.

In the past decade, there has been a substantial increase in the number of public inquiries in Australia and there is a higher risk of businesses in Australia being called to give evidence before them.

If it is necessary to engage with a Commission, it is important to understand that each Inquiry will be situationally dependant, with the Commission having significant discretion concerning its operating procedures, inquiries and conduct of hearings. That said, a business or key witness engaging with a Commission can expect:

- a rigorous, intense process;

- high levels of public scrutiny;

- the involvement of persons who may not have had much exposure to this legal process, and the inevitable consequences of those individuals being placed in an unfamiliar, uncomfortable environment of scrutiny and formality; and

- a risk of adverse publicity and, in the long run, potential successive civil litigation, regulatory investigation or prosecution, should serious adverse findings be made that may encourage relevant third parties to gather evidence and pursue redress.

Whilst there can be no single play book, the above is a framework that in our experience may prove useful to reflect upon when developing a response posture and process for dealing with a Commission.

[1] See for example discussion in Re Equiticorp Finance Ltd (1992) 27 NSWLR 391; Legal Profession Uniform Law Australian Solicitors’ Conduct Rules 2015, rule 24.

[2] Legal Profession Uniform Law Australian Solicitors’ Conduct Rules 2015, rule 25.

To download a PDF version of this article please click here.

For a confidential discussion concerning any Commission process, contact our Adam Merlehan – Managing Director.

Merlehan Group is a leading multi-disciplinary law firm comprised of top tier legal professionals with combined decades of experience advising some of the largest corporations in Australia, and specialist expertise in guiding businesses through controversy and business critical issues when they arise, including those compelled to give evidence before Commissions of Inquiry.