For decades into the future, Steve Jobs and his rise to the top of the corporate world will be studied as a contemporary corporate leadership and strategy case study in business schools throughout the world.

Jobs’s biography authored by Walter Isaacson provides fascinating insight into the complex person that Jobs was and the business strategy and leadership style he adopted.

Jobs’s story is well known.

Concisely, Jobs, a college dropout, tasted his first success building a computer company (Apple) from scratch in his garage with his close friend Wozniack. After Apple became successful as a computer company he became a spectacular failure as a leader in his first attempt, which resulted in his exile from the very business he founded. He somewhat failed again when he built another company (Next) that was not very successful and was later acquired by Apple. He then built the world’s most successful animation company, Pixar, and orchestrated its merger with Disney for a deal worth $7.4bn. After Apple’s performance tanked under its CEO John Scully (who was picked over Jobs, resulting in Jobs’s departure from the business), Jobs returned and led its transformation from a business that had lost its way and was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy into the world’s most valuable company.

Jobs’s transformation of Apple was achieved via:

- corporate strategy simplification

- an intense focus on product quality

- simplifying the user experience

- innovation focused on the intersection between liberal arts and technology (making computers sexy)

- a liberal dose of perfectionism.

To say Jobs was a pioneer, is an understatement.

His fingerprints are all over:

- The iPod, iPhone, iPad and iMac

- The iTunes Store (and its saving of the music industry)

- Apple’s App Store (and its proliferation of a new market for applications and resulting unprecedented innovation and content creation)

- Pixar animation’s movie successes of Toy Story, Finding Nemo, Cars, Ratatouille etc

- iCloud (and its simplification of cloud computing and device synchronisation across the Apple range)

- the ‘Apple Store’ concept, (and its revolution of the role of a retail store in defining a brand and customer experience)

He revolutionised (or ‘disrupted’, if you are a fan of the latest buzzwords) the music, computing, animation, retail and software industries.

His story is a remarkable one.

What key lessons (of which there are many) can be learned from his story? Here are four:

Lesson #1: The most effective corporate strategy is a simple, easy to communicate one.

Lesson #2: Criticism, accountability and honest robust debate is a healthy thing for high performing teams.

Lesson #3: Don’t ask your customers or clients what they want. The challenge is to know what your customers want before they do.

Lesson #4: The definition of a genius is the capacity to make the complex simple.

Each are explored below.

Lesson #1: The most effective corporate strategy is a simple, easy to communicate one. One that is capable of focusing the minds and efforts of people towards a common goal.

When Jobs returned to Apple, Apple’s strategy was confused. Apple was carrying a huge number of confusing product lines. Jobs started asking simple questions of his leaders: “Which products do I tell my friends to buy?”

He knew Apple’s current strategy was doomed when he couldn’t get a straight answer to that question.

Jobs, fed up, reportedly responded by audaciously drawing the following on a whiteboard in a product strategy session:

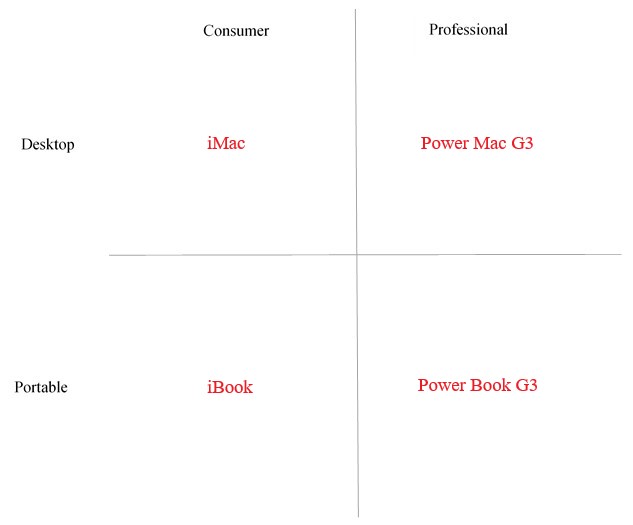

He reportedly challenged Apple’s product designers and engineers to focus on developing four products to fill this chart, and not work on anything else.

The beauty of this simplicity was that it aligned the minds of everyone within the business and directed all business decisions towards a very clear, common, strategic purpose and goal. It challenged the thinking of Apple’s top people and focused effort through a single, uncomplicated prism.

Jobs ruthlessly went about slashing products (and headcount) that were not aligned with this new strategy, including jettisoning Apple’s production of laser printers and virtual assistance software. The boldness of his vision and this execution towards it reportedly saved Apple from bankruptcy. It resulted in the following:

The simplicity and audacity of Jobs’s “dumbed-down” strategy sparked the beginning of a wave of amazing product developments and successes under his watch. It made and continues to make sense: an organisation is a collective of individuals working together in a common pursuit, yes organisations own capital assets but without people, they don’t function. Keeping things simple so that the strategy and goals are clearly understood by the talent in the business that drives the organisation allows intent and unified focus of effort with resulting exceptional results.

Lesson #2: Criticism, accountability and honest robust debate is a healthy thing for high performing teams, particularly among a team of ‘A-players’

Jobs’s sometime vitriolic criticism of his people is legendary (and not in a positive way).

By all accounts, including by the man himself, Jobs was an exacting and difficult person to work for. If Jobs’ did not like something you did, you knew about it, bluntly.

He consciously assembled a team of A-players, drove B-players out of the business and drove the A-players hard to deliver the results required (sound familiar?), often resulting in them achieving things they themselves never thought possible.

Jobs demanded brilliance from his people, and he got it.

Jobs is quoted in the last chapter of Isaacson’s book reminiscing about his approach to managing people at Apple:

“If something sucks, I tell people to their face. It’s my job to be honest… That’s the culture I tried to create. We are brutally honest with each other, and anyone can tell me when I am full of shit and I can do the same…

I was hard on people sometimes, probably harder than I needed to be…

I figured that it was always my job to make sure the team was excellent, and if I didn’t do it, nobody was going to do it…

I have learned over the years that when you have really good people you don’t have to baby them. By expecting them to do great things, you can get them to do great things.”

This view is supported anecdotally by many who worked for him who have since commented on what it was like to work for Jobs. Some recall working for him as extremely hard, but the most rewarding experience of their lives.

Jobs’s view on the role of conflict in high performing teams is supported by research.

Low levels of conflict can be destructive to teams, producing sub-optimal decision making and poor strategic thinking.

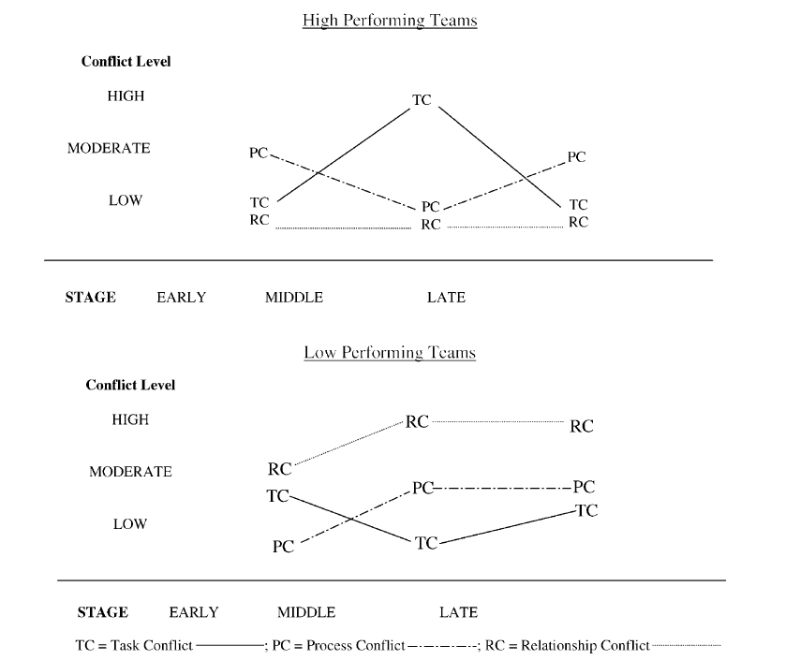

Jehn and Bendersky in their study (see reference below) on the role of intragroup conflict in organisations identified three forms of intragroup conflict:

- Relationship conflict: interpersonal incompatibilities among group members.

- Task conflict: disagreements among group members about tasks being performed.

- Process conflict: disagreement about the strategies for achieving a specific task, not about the substance of the task itself.

They observed that high performing teams typically follow a pattern of healthy process conflict at the outset of a task, high levels of task conflict during the core of the task and low levels of relationship conflict at all times.

They contrasted this with the levels of conflict that typically persist among low performing teams as follows:

(Reference 1 below)

The point is: it is healthy to robustly debate the strategy/process for achieving a task at the outset of that endeavour and then, throughout that endeavour, to debate the task content itself.

It is also perfectly healthy to have a team culture where this robust level of debate (whilst preserving respect) is championed. To do so produces high performing teams, increases productivity and creativity and improves strategic decision-making. Likewise, driving accountability into teams is a good thing. It ensures outcomes are delivered, team members bring their ‘A-Game’ and stamps out shirking.

One consequence of a lack of constructive conflict is ‘groupthink’, where team members are so concerned with staying within their ‘comfort zone’ and artificial group ‘harmony’ that this results in dysfunctional or irrational decision-making. At its extreme, some research has suggested groupthink within NASA may have contributed to the Challenger space shuttle disaster that claimed seven lives.

Some executive teams, often longstanding ones, and in longstanding businesses, routinely avoid conflict at all costs because it is viewed as ‘uncomfortable’ and because the culture has been an artificially harmonious one for a long time. If this describes your team, you are missing an opportunity to lift your team’s performance and achieve great things. You may benefit from stimulating more ‘constructive’ conflict by building a culture where constructive conflict is celebrated, provided safeguards are agreed to avoid unnecessary relationship conflict (such as the maintenance, at all times, of mutual respect). As with any organisational change, it will take time to transform the culture towards accommodating and ultimately championing constructive conflict, however the result may be well worth it.

It is interesting to note that reports are now circulating from former employees that Apple has lost its way under Cook’s leadership because, in essence, people are expected to ‘not worry about what others are doing’ and focus on their own job. If those reports are true, it speaks volumes about the value of fostering constructive challenge in teams and the consequence of losing it.

Lesson #3: Don’t ask your customers or clients what they want. The challenge is to know what your customers want before they do.

Jobs despised marketing focus groups.

In Isaacson’s book, Jobs is quoted as saying:

“Some people say, ‘Give the customers what they want.’ But that’s not my approach. Our job is to figure out what they’re going to want before they do. I think Henry Ford once said, ‘If I’d asked customers what they wanted, they would have told me, “A faster horse!”’ People don’t know what they want until you show it to them. That’s why I never rely on market research. Our task is to read things that are not yet on the page.”

His sentiment is simple but profound, and it transcends industries.

For example, in the professional services context (my context), if you were to ask your client “what is it you want from me?” you would:

- be starting a conversation today that already started about 3 years ago in the face of increased competition in our sector; and

- find it difficult to extract an insightful answer beyond “more service, at a lower cost”.

It is a lazy question.

As a professional advisor, my job is not to ask my clients what they want. My job is to ask myself:

- What problems are my clients going to face and need to solve in the future?

- What critical tasks or transactions are they going to need to execute in the future?

- How can I build unique capability in my team to help them solve those problems or execute those transactions in a way they cannot easily find elsewhere?

Answering those questions unlocks value and future relevance.

Jobs’s mindset is a powerful one.

Lesson #4: The definition of a genius is the capacity to make the complex simple.

Jobs was tenacious in his pursuit of simplicity, not just in the user experience of Apple’s products but also their aesthetic appeal.

He hated technology that was hard and not intuitive to use.

Jobs participated in product reviews at Apple personally and demanded simplification if he thought something was not needed or the product was not intuitive to use. He often came up with ideas himself for simplifying the product experience that astounded his talented designers.

He was across the bigger picture and the minute detail.

From the sleek buttonless design of the iPhone, to the simple scroll wheel navigation on the iPod, to the minimalist design of the all-in-one iMac; if something could be simplified, that is what Jobs demanded.

He continually challenged his team to simplify.

This is not to say Apple’s devices are incapable of complex functionality. The iPhone is of course a phone but also an immensely powerful and complex computer that looks unassuming and fits within the palm of your hand (and is only occasionally used for phone calls!). Despite its immense computing power and capacity to perform complex functions, it is remarkably simple to use. Adopting Lesson #3 above, how many customers (if asked) would have been able to articulate that this was the type of device they so needed in their lives?

Simplifying the complex resonates.

I have been fortunate enough in my career to work with some of Australia’s leading Queens Counsel , some of whom are now judges, and very good ones.

What has impressed me most during those opportunities and what I have always taken away as a trait to aspire to was not the eye-watering fees they are capable of charging per day or their capacity to masterfully absorb complex facts or their ability to recite huge amounts of legal theory on cue; but it was always their unique competence to distil very complex legal issues into simple, clear, easy to understand propositions. Leaving aside their intellectual rigour (which is assumed), the ability to make the complex simple is something you are always prepared to pay good money for. It is the hallmark of people who know what they are talking about and it’s impressive. Jobs understood this and Apple’s products under his leadership achieved remarkable success as a consequence of this time honoured vision.

In short, Albert Einstein’s quote continues to ring true today:

“The definition of genius is taking the complex and making it simple”

…

References:

1. Jehn, K. and Bendersky, C. (2003). Intragroup Conflict In Organizations: A Contingency Perspective On The Conflict-Outcome Relationship. Research in Organizational Behavior, 25, pp.187-242.

2. Isaacson, W. (2011). Steve Jobs. New York: Simon & Schuster.